About the Corpus

Introduction

The Electronic Corpus of the 17th- and 18th-century Polish Texts, briefly called KorBa1, is the most important result of two projects carried out in 2013-2018 and 2018-2023. They were conducted by the Department of the History of the 17th- and 18th-century Polish of the Institute of the Polish Language of the Polish Academy of Sciences in cooperation with the Linguistic Engineering Group of the Institute of Computer Science of the Polish Academy of Sciences. Information on each of these projects can be found in the "KORBA 1 Project" and "KORBA 2 Project" tabs.

In 2018, the first version of the corpus was made available, covering texts from the years 1601-1772 and containing almost 13.5 million tokens (as understood by the creators of the National Corpus of Polish, hereinafter: NKJP). The currently presented corpus covers a period of two centuries, and its volume has been increased to almost 27 million tokens. During the second mentioned project, the corpus was integrated with other sources for research on the Polish language of the 17th and 18th centuries, namely the Electronic Dictionary of the 17th- and 18th-century Polish (e-SXVII), the digitized catalogue of this dictionary and the Digital Library of Polish and Poland-Related News Pamphlets from the 16th to the 18th Century (CBDU). The website of the Polish Language of the 17th and 18th Centuries. Dictionaries, Corpora, Resources, which makes the simultaneous search of all these resources possible, was created as well.

Data collected in KorBa are available via the MTAS search engine, which uses Corpus Query Language (CQL). CQL allows you to search for individual tokens or their sequences, the form of which can be specified in detail using the attributes assigned to each token. Users can use the query builder, which allows you to replace CQL symbols with commonly known grammatical terms. The texts encompassed in the corpus are presented in both transcribed and transliterated forms. Rich metadata, structural and linguistic tags and morphosyntactic annotation and lemmatization allow for a wide range of queries, as well as filtering the search results and locating their position in the source, up to the exact page number. A detailed description of the capabilities of the MTAS search engine and query language can be found in the "Instruction" tab.

Our corpus represents an attempt at building a relatively large corpus of historical Polish texts that would meet all requirements set before modern resources of this type, while being designed with multidirectional research in mind. Our corpus allows easy access to the Polish national heritage left behind by the Baroque and Enlightenment eras and the evolution of the Polish language over the ages. Most importantly, however, the corpus can serve as a new tool for research in many branches of the humanities, such as linguistics, literature studies, culture studies, history and sociology. It allows one to easily search through and analyze historical Polish texts.

KorBa and other Polish corpora

Until 2013, Polish language corpora were, for the most part, limited to modern texts. Work on each corpus was entirely separate, until in 2007-2012, thanks to an initiative by the Institute of Computer Science PAS (which coordinated the project), the Institute of Polish Language PAS, Polish Scientific Publishers PWN and the Department of Computational and Corpus Linguistics at the University of Łódź, realized as a Ministry of Science and Higher Education project, the National Corpus of Polish (NKJP) was created. It is currently the largest Polish language corpus, but it is mainly focused on relatively modern texts. KorBa was conceived as a historical supplement – the first stage in extending the National Corpus’ range to include older texts. We hope that, in the near future, it will be possible to create (sub)corpora encompassing the entire history of written Polish. Work on such corpora has already begun. A so-called corpus of Old Polish texts (up to the year 1500) has already been created by the Institute of Polish Language, PAS, however at this moment it does not contain any annotations (neither structural nor morphosyntactic), it also offers no search engine. This corpus is a good starting point for creating an Old Polish corpus in the sense commonly accepted today. Work on creating such a corpus is ongoing in a team led by Ewa Deptuchowa (cf. Klapper, Kołodziej 2014; Klapper, Kołodziej 2015; Deptuchowa et al. 2020). The first corpus of old Polish texts that fits the modern standards for such resources was created for the international IMPACT (Improving Access to Texts) project. Work on this corpus lasted from 2009 to 2012 and was carried out in the Formal Linguistics Department of the University of Warsaw by a team under the supervision of Janusz S. Bień. One characteristic of this corpus, stemming from the overall goals of the project, is the extreme closeness of its transliteration to the original texts – the corpus differentiates between all shapes of graphemes present in the source texts (cf. Bień 2014)2. During the years 2013-2016, the Institute of Polish Language of Warsaw University created a comparatively small corpus of 19th-century texts3 (from the years 1830-1918). The Institute of Literary Research of the Polish Academy of Sciences has also began work on a corpus of 16th-century Polish texts. In addition to corpora that, like those mentioned above, meet the requirements of representativeness and sustainability (or at least strive to meet them), the so-called opportunistic corpora incorporating any available text have been developed. Such corpora include PolDiLemma, collecting texts from the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, and the Corpus of 19th-century texts, covering the period 1800-1933.

Currently, i.e. at the beginning of 2024, when we make available the Electronic Corpus of the 17th- and 18th-century Polish Texts, which is twice as big as before, there are many more corpora collecting old Polish texts4 (including e-Rotha, i.e. Electronic Repository of Greater Poland Oaths), but still KorBa is the most extensive and best-developed corpus of historical Polish. Perhaps in the near future, the National Diachronic Corpus of Polish, which has been planned for several years, will be created, and then KorBa will become part of it (cf. Król et al. 2019).

The creators of NKJP set many of the standards for Polish corpus linguistics; they also created the IT tools necessary for its construction and for easy access. It should come as no surprise then that we used the NKJP as a model for the KorBa project's approach to tool creation and have ensured that our corpus will be compatible with NKJP in the future, both in terms of its linguistic and structural aspects. In particular, we have strived for maximum consistency with the NKJP's morphosyntactic tagging system. However, for obvious reasons, it was not possible to use the same set of tags as in a corpus of modern texts. Some changes were necessary, as 17th and 18th century Polish, on the one hand, distinguished between some grammatical categories (or their values) that are not present in modern day Polish, while on the other hand it lacked some categories characteristic of the modern Polish language. The full set of morphosyntactic tags is presented in detail in "Instruction".

A portion or portions of each text found in the full KorBa corpus are also included in the manually annotated subcorpus (version 2.0; the previous version, 1.0, will also be available but only until the end of the year 2025). The manually annotated subcorpus 2.0 contains a total of 850,000 segments. This subcorpus has two purposes. First, it was used to train the KFTT tagger for automatic annotation of the entire corpus. Then, the manually annotated subcorpus was intended to be and still is a gold standard resource in terms of transcription and morphosyntactic annotation, and therefore intended for the analysis of more difficult linguistic phenomena.

The text selection process

During conceptual work, we have taken into account the generally accepted essential attributes of language corpora – balance and representativeness. In the case of historical material, however, such attributes are not necessarily possible to achieve fully. In the end, the choice of texts was influenced by various criteria, including ones not related to language.

The contents of the corpus were determined by limited knowledge about the whole of the era writing (and not only the texts which were preserved until the modern day). Naturally, most of the preserved texts are works of literature, as they were treated with more care, often reprinted and passed down from generation to generation as an element of cultural heritage. During work on the corpus, this fact has made it impossible to apply the principle used for most modern corpora, according to which literary fiction should only comprise up to 20% of a given corpus. Much of the knowledge that plays a key role when constructing a modern corpus is very limited for the 17th-18th century and must often be inferred indirectly. A text's popularity may be inferred from the presence of multiple editions, or from references in other texts of that era.

Authors of historical corpora are bound by many such constraints to available materials. They may only use one communication channel – written sources, and only ones that were preserved over hundreds of years. There are, however, also some advantages to working with historical material. Researchers have at their disposal a closed set of texts, one that has already finished its evolution – in comparison, a corpus of modern texts will always be open. Using historical material also results in a research perspective that is distanced by time, facilitating easier synthesis.

The limited availability of materials has forced us to utilize many different types of sources, some of which are inherently flawed. The most desired sources include original historical prints and manuscripts. These materials were, however, especially difficult to prepare, since they had to be transcribed into a digital form, which is an expensive and time-consuming task. In the second edition of the project, we used models for automatic handwriting analysis (Handwritten Text Recognition - HTR), trained to read texts from the 17th and 18th centuries. The extraction of sources in their original form was facilitated by a significant increase in the number of electronic editions of works posted in digital libraries, as a result of which we had easier access not only to the already known, classic works, but above all to manuscripts, rare editions and documents stored in foreign libraries. A part of the corpus consists of transliterated texts of old prints, made available to us in an electronic form by the performers of the Polish part of the international IMPACT project (a collection of approximately 1.6 million tokens).

The corpus also includes editions of Baroque and Enlightenment texts from later times. The editions from the 19th century are particularly far from perfect (due to the then accepted standards of significant publisher interference into published texts). However, we included them since they were often the only preserved forms of interesting texts worth introducing into the corpus. Electronically prepared contemporary editions of texts from the 17th and 18th centuries constitute another type of included sources. Technically, they were the most convenient ones as, due to their electronic form, they could be easily placed into the corpus. Nevertheless, even in this case, there were difficulties: on the one hand, of a legal nature (limitations resulting from copyright law), and on the other, of a linguistic and editorial nature, caused by the fact that modern publishers often use not one, but several editions from the era as the basis for editing. In general, we followed the principle that it is better to include a text in a non-period form than to exclude it from the corpus. All sources are provided with detailed bibliographic information, including an information about the source type (a transliterated manuscript or print from the period or a later 19th, 20th or 21st-century edition).

In order to keep the corpus balanced, we have decided that very long texts (such as the so-called Gdańsk Bible, Syreniusz’s herbarium, the collected sermons of Birkowski, Młodzianowski or Starowolski) will only be included in the form of selected fragments. The metadata set contains information about which fragment was included in the corpus.

In choosing texts for KorBa, we have considered the following types of variation: chronological, geographical, genre and subject matter.

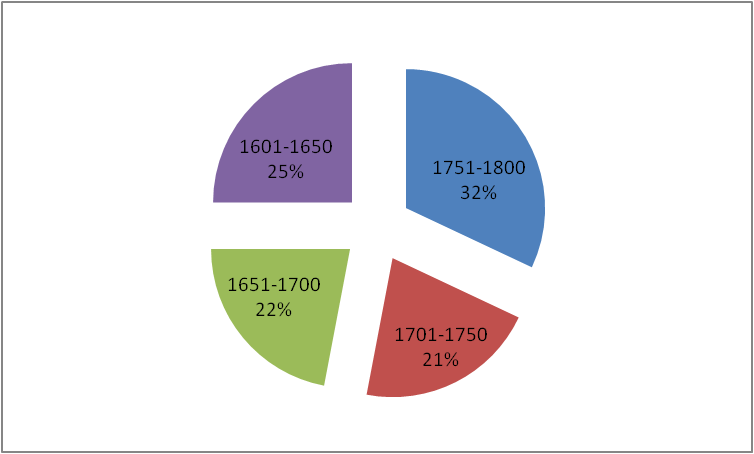

The adopted criteria regarding chronological diversity assumed striving for a balanced quantitative representation in the corpus of four subperiods: 1601-1650, 1651-1700, 1701-1750 and 1751-1800. Additionally, we had in mind the division into the Baroque (1601-1740) and Enlightenment (1741-1800) subcorpora. Of course, the adopted time caesuras are artificial and only serve organizational purposes. The quantitative criterion also had to be adjusted many times due to other important factors. For example, the first half of the 17th century and the last quarter of the 18th century saw the creation of many important, canonical texts for the era that had to be included in the corpus. In turn, in the first decades of the 18th century, the decline of culture was accompanied by a significant reduction in original, interesting writing. The printing market of that time was monopolized by monastic printing houses focused on achieving their own goals in writing production, which is why the majority of published works of that time comprised various types of religious writings. The inclusion of manuscript texts proved helpful in diversifying the topics of sources from that period. These included romances that circulated between courts and literary salons as copies of published (or unpublished) translations often made by women. The anonymous History of Alkamen, the king of the Scythians, and Menalippa, the princess of Denmark, translated by Balbina Pac née Wołłowicz can serve as an example. Moreover, the Sejm texts and historical texts in general remained in the manuscripts, such as the Summary of Polish and Foreign History by Antoni Jan Czeczewicz.

At the stage of balancing the corpus, we decided that sources without an expressis verbis annual date written on the title page should not be assigned a year determined on the basis of bibliography and library catalogues, but a period approximated to a decade. We applied this principle even in the case of dramas published in the second half of the 18th century, the title pages of which indicated the time the play was performed, not the year of publication. Only in a few cases, in order to maintain clear chronological divisions into half a century and into the Baroque and Enlightenment subcorpora, we slightly modified this rule, rounding the time of publication to less than a decade, but still without a clear indication of the year.

The chronological representation of the texts in KorBa is presented in the charts below:

In terms of geographical diversity, the content of the corpus includes texts from all regions where the Polish language was used, usually distinguished in the historical research of this period, i.e. Masovia, Lesser Poland, Greater Poland, the Ruthenian Lands, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Podlasie, Silesia, Livonia, Pomerania and Prussia. The number of texts from specific regions included in the corpus remains very diverse. It is, to a large extent, a reflection of the writing activity of individual centers, and to an even greater extent of their publishing activity. It should also be mentioned that some sources have an unknown region of origin because they had no information about the place of their publication on the title page. In turn, we assigned the "other" region to the texts that had a double place of publication: Warsaw and Lviv.

It is worth noting that after a thorough query, we have standardized the names of the printing houses. Providing the names of publishing houses in the version originally entered on the title page could be misleading, so individual printing houses were identified as individual corporate entities and then assigned modernized names according to a uniform code. As a result, the entries: "U XX. Schol Piarum" ["At Priests Schol[arum] Piarum"] and the "Drukarnia Akademii Pijarów" ["Piar Academy Printing House"] are identified as one publishing center: "Drukarnia Pijarów" ["Piar Printing House"]. Also "Typografia Bractwa św. Trójcy" ["Typography of the Brotherhood of St. Trinity"], "Drukarnia św. Trójcy" ["St. Trinity Printing House”] and "U OO. Trynitarzy” ["At Fathers Trinitarians"] gained one common name: "Drukarnia Trynitarzy” ["Trinitarian Printing House"]. That action also resulted in the empowerment of women who, after the death of their husbands, ran printing houses on their own. On the title pages they appear as nameless widows, while in the corpus they are presented with their first and last names, e.g. the entry "U Wdowy Jana Rossowskiego" ["At Jan Rossowski’s Widow"] was labelled as "Drukarnia Katarzyny Rossowskiej" ["Katarzyna Rossowska's Printing House"].

The geographical variation of texts in KorBa can be seen on the following map:

Genre variation is another factor that influenced out choice of texts for the corpus. The genologies and typologies used for constructing modern corpora are not ideal for use on historical material. For this reason, we have deemed it necessary to prepare a typology that would meet the requirements of KorBa. It is made up of several levels.

At the highest level, the texts are divided into rhymed (which constitute 16,53% of segments in the corpus), non-rhymed (80,63% of segments) and mixed (2,85% of segments). Information on this subject is particularly important, as the rhythm and rhyme of a poem may influence the inflectional form of any word a corpus user might search for.

The second level is the division between literature and non-literary texts. Literature has been divided further, in accordance with literary tradition, into epic, lyric, drama and syncretic texts. These categories, of course, contain texts representative of literary genres characteristic for the epoch. The detailed classification of non-literary texts corresponds with the typology used in NKJP, as much as it is possible in the case of historical texts. Due to difficulties with categorizing the Bible, we have decided to treat it separately from all other texts.

While expanding the corpus, we introduced some changes that classify source texts according to their genres in a more orderly and balanced way. Combining funereal genres into one category of "lamentations, laments" was one of the alternations we made. Due to the presence of various types of poems, we decided not to distinguish epic, heroic, or philosophical poems separately and grouped them into the common category of "poems". We have also organized categories that are too general or overlap with others, e.g. "privileges and deeds of granting", "prenuptial agreements", "agreements" were divided into "civil contracts" and "legal acts"; in turn, we changed "treaties" and "lectures" to "scientific dissertations". Moreover, additions to the source material, especially from the end of the 18th century, necessitated adding new genres, such as: "dramas", "novels", "announcements", "proclamations".

Our intention was to show the greatest possible diversity of genres reflecting the state of literature at that time. Therefore, we have distinguished, among others, "nativity plays" as a special type of dramatic works. Yet, in turn, we understood "song" broadly, more as a type of text, as it used to be perceived in the 17th and 18th centuries (Dobak 1991: 396). The result of the work is a concise list of genres, which, however, have varying degrees of detail.

It should also be mentioned that for technical reasons we had to select only one genre category for each text. In the case of collections of small works containing texts of various genres, e.g. sonnets and idylls, we have designated a new category "various lyrical".

The detailed list of types and genres is as follows:

| types | genres |

|---|---|

| epic | fables, hagiographies, novels, parables and specula (mirrors), poems, romances |

| lyric | dumas, carols and folk carols, emblemas, epithalamia, epigrams, threnodies and laments, odes, panegyrics, songs, riddles, psalms, sonets, various lyrical pieces |

| drama | comedies, dialogues, dramas, intermèdes, libretti and scripts, nativity plays, tragedies |

| syncretic texts | anecdotes, pastorals, satires |

| scientific-didactic & information-guide texts | calendars, catechisms, culinary recipes, encyclopedias and compendiums, guides, phrasebooks, regulations, scientific dissertations, textbooks |

| persuasive texts | introductory texts, liturgical books, prayers, political speeches, proclamations, proverbs, sermons, writings on political and social topics, writings on religious topics, speeches for various occasions |

| factual literature | accounts of events, biographies, chronicles, descriptions of journeys, geographical descriptions, memoirs, rolls of arms |

| official & secretarial texts | annoucements, city laws, civil contracts, court documents, documents of regional parliaments, inventories, judicial records, legal acts, official letters, other Seym texts, Seym bills, Seym journals, testaments |

| press releases & leaflets | press news |

| letters | letters |

| Bible | Bible |

The summary below illustrates the percentage of corpus tokens in the distinguished text types:

When building the corpus, the assumption was to reflect the topics present in the literature of the era. The registration of vocabulary relating to fields that were popular at that time but are now peripheral (e.g. alchemy, astrology, herbalism) was a particularly important task. It was also crucial to capture the beginnings of interest in new thought trends or disciplines (such as aviation, metallurgy or sociology). As a result, the list of thematic categories includes more general items (e.g. customs, social issues, science), but also highly specialized ones (e.g. hunting, anatomy, tanning).

In the opinion of the authors of the Electronic Corpus of the 17th- and 18th-century Polish Texts, the documents collected in both editions of the corpus well reflect the writing in the Baroque and Enlightenment eras. They appropriately show both thematic interests and the intensity of interest in certain genres at a given time, and, at the same time, do not ignore the presence of genres that were less represented.

Bibliography

- Bień, J.S., 2014. The IMPACT project Polish Ground-Truth texts as a DjVu corpus. „Cognitive Studies | Études Cognitives” (14). pp. 75–84.

- Deptuchowa E., Jasińska K., Klapper M., Kołodziej D., 2020. O projekcie Korpusu Polszczyzny do 1500 roku, „Poradnik Językowy” 8, pp. 7–16.

- Dobak, A., 1991. Pieśń, [in:] T. Kostkiewiczowa (ed.), Słownik literatury polskiego oświecenia, Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, Wrocław – Warszawa – Kraków pp. 395–400.

- Gruszczyński, W., 2020. Korpusy językowe narzędziem pracy historyka języka, [in:] A. Hącia, K. Kłosińska, P. Zbróg (ed.), Polszczyzna w dobie cyfryzacji, Wydawnictwo PAN, Warszawa, pp. 255–265. DOI: 10.24425/137351

- Klapper M., Kołodziej D., 2014. Elektroniczny Korpus Tekstów Staropolskich do 1500 r. Perspektywy i problemy, „Prace Filologiczne”, no 65, pp. 203–210.

- Klapper M., Kołodziej D., 2015. Elektroniczny Tezaurus Rozproszonego Słownictwa Staropolskiego do 1500 roku. Perspektywy i problemy, „Polonica”, no 35, pp. 87–101. https://polonica.ijp.pan.pl/index.php/polonica/article/view/76.

- Król, M., Derwojedowa, M., Górski, R.L., Gruszczyński, W., Opaliński, K., Potoniec, P., Woliński, M., Kieraś, W., Eder, M., 2019. Narodowy Korpus Diachroniczny Polszczyzny. Projekt, „Język Polski” XLIX, pp. 92–101.

- Pastuch, M., Duda, B., Lisczyk, K., Mitrenga, B., Przyklenk, J., Sujkowska-Sobisz, K., 2018. Digital Humanities in Poland from the Perspective of the Historical Linguist of the Polish Language: Achievements, Needs, Demands, „Digital Scholarship in the Humanities”, vol. 33(4), pp. 857–873. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqy008

endnotes

- The acronym comes from Korpus Barokowy, which means The Baroque Corpus. It was used during the first project when the corpus contained mainly texts from the Baroque era. Currently, it includes texts from two eras, the Baroque and the Enlightenment, but we have retained the old acronym due to its widespread use in the scientific community.

- The corpus is currently available at: https://szukajwslownikach.uw.edu.pl/IMPACT_GT_1/ and https://szukajwslownikach.uw.edu.pl/IMPACT_GT_2/.

- Cf.: http://www.f19.uw.edu.pl/ i https://szukajwslownikach.uw.edu.pl/f19/.

- Gruszczyński (2020) and Pastuch at al. (2018) provide information about some of them.